IHT Special

Years of Torture in Iran Comes to Light

By KRISTEN McTIGHE

Published: November 21, 2012

PARIS — Houshang Asadi was a Communist journalist thrown into the cold confines of Moshtarek prison in Iranwhen he found an unlikely friend in the tall, slender Muslim cleric who greeted him with a smile.

Imprisoned together in 1974, under the rule of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, they found common ground in their passion for literature. They shared jokes, spoke of where they came from, their families and falling in love. Mr. Asadi, who did not smoke, would give cigarettes to his cellmate who, uncharacteristic of a cleric, did. On days when Mr. Asadi felt broken, he said, the cleric would invite him to take a walk in their cell to brighten his spirits.

So, when his release came six months later and the cleric stood cold and trembling, Mr. Asadi gave him his jacket. “At first he refused it, but I told him I was going to be released,” Mr. Asadi recalled. “Then we hugged each other and he had tears coming down his face. He whispered in my ear, ‘Houshang, when Islam comes to power, not a single tear will be shed from an innocent person.”’

What Mr. Asadi found unimaginable was that the cleric would become president of the Islamic Republic that later imprisoned him again, sentenced him to death and brutally tortured him for six years in the same prison. Today that same cleric is the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

continue

TELEVISION:

> ZEIT IM BILD (Mi., 01.06.2011):

http://tvthek.orf.at/programs/1211-ZIB-2/episodes/2302877-ZIB-2/1700937-Auszeichnung-fuer-iranischen-Schriftsteller

> SEITENBLICKE (02.06.2011):

http://tvthek.orf.at/programs/1360-Seitenblicke/episodes/1698831-Seitenblicke/1701759-Buchlieblings-Gala-2011

> SOMMERZEIT (Fr., 03.06.2011):

http://tvthek.orf.at/programs/71919-Sommerzeit/episodes/1701053-Sommerzeit/1704429-Buchliebling-2011

RADIO:

> KULTURJOURNAL (Mi., 01.06.2009)

http://oe1.orf.at/konsole?show=ondemand

>> the way to find the program:

1.) click on Mi

2.) scroll down till 17:09 Kulturjournal

3.) click on Player starten (= white shaft on black button)

>> second story

PRINT:

find attached the stories in “KURIER”, “STANDARD” and “ÖSTERREICH”

(Originals will follow by post with all the material)

http://www.wienlive.tv/kultur/tv/1864

WEB:

http://www.apa-fotoservice.at/galerie/1437 (= free download for fotos;

Copyright: APA/echo/Schedl)

http://oe1.orf.at/artikel/278345

http://derstandard.at/1304553381276/Ich-verwandelte-mich-in-das-schlimmste-Tier-der-Welt

http://difa-aachen.de/menschenrechte/352-buchpreis-fuer-menschenrechte.html

HOUSHANG ASADI was born in Tehran in 1950. Prior to the Islamic revolution, he spent many years as the Deputy Editor of Kayhan, Iran’s largest daily newspaper. For the next 12 years, he was Editor-in-Chief of GozareshFILM (Film Report), the country’s largest circulation film magazine. He is the author of several novels, plays and films, and has translated works into Persian by writers including Gabriel Garcia Marquez and T S Eliot.

In 1983, following the Iranian government’s crackdown on all opposition parties, Asadi was pushed blindfold into an unmarked car and kept in solitary confinement for over two years. Moshtarek prison in Tehran is one of the country’s most infamous institutions. He was subjected to brutal torture and imhuman degradation. Asadi was convinced this was a case of mistaken identity. As a supporter of the Islamic Revolution he had shared a cramped prison cell with the Ayatollah Khamenei (Iran’s current Supreme Leader) in the 70s, and considered him a close friend.

Asadi was forced to ‘confess’ to being a spy for the British and Russians. Hauled before a sham court, he narrowly escaped execution. Asadi was sentenced to 15 years before being released after 6. After escaping Iran, Asadi and his wife now live in exile in Paris, where he founded the infuential Persian news website, Rooz Online.

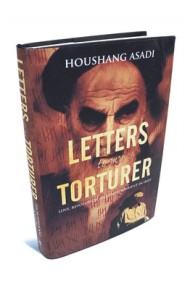

THE BOOK

LETTERS TO MY TORTURER details the events following the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Houshang Asadi recounts in horrific yet gripping detail, the reality of life as a prisoner in one of the most hostile prisons in Iran – and probably the world. As a healing exercise, a way to purge himself of the hatred towards Brother Hamid, the perpetrator of torture in the prison, Asadi began writing Letters to my Torturer, in the form of correspondence to Brother Hamid. It was extremely painful re-living the terrible experience, the beatings, the whippings, the times he was suspended by his ankles from the ceiling for hours on end. When Asadi began the manuscript for Letters to My Torturer, the memories were so shocking that he had a heart attack. But he was determined to keep going. As the first draft of the book was finished in 2009, Iran once again descended into political chaos.

‘At the height of one of his torture sessions, Brother Hamid asked me: If one day things change and we end up being your captives, what will you do to us? My answer is this: we will demolish all the world’s infamous prisons of torture and we will sentence the intelligence officers and interrogators to go to their ruins to plant flowers and sing love songs. And the sham trials, the torture and all forms of degrading and inhuman treatment will at last be a thing of the past’. Houshang Asadi, March 2010, Paris.

—————————————-

Radio Free Europe:Recalls Torture, Sharing Cell With Supreme Leader

In an interview with RFE/RL correspondent Golnaz Esfandiari, Asadi says prisons in the Islamic republic and torture methods used against political prisoners are far worse than they were under the shah’s rule. Asadi also speaks about one of his former cellmates, Ali Khamenei, who is now Iran’s supreme leader, as well as his torturer, “Brother Hamid,” whom he says later became a diplomat.

Iranian : Mr. Houshang Asadi, Congratulations!

http://www.iranian.com/main/blog/sheila-k/mr-houshang-asadi-congratulations

W hen your grade teacher told your mother, “Your son will be a great writer,” he must have had a strong premonition. You are a GREAT writer and a GREAT hero. Your survival, your endurance, your compassion in the face ofthe evil torturer, your kindness to your inmates, your amazing memory, your truth, your love for your wife, …and your passion to tell the story of yourself and thousands of other innocent victims of IRI in and of itself is superbly heroic.

When I first began to read your book, Letters to My Torturer, I almost put the book away unfinished. At times I felt my chest tightening; I was angry, emotional, and horrified. As I came to my senses, I noticed two things: I was being selfish and that your writing is so good that I had found myself in your shoes (or slippers). I’d find myself standing in your interrogation room while you were hanging by your wrists and I could feel your shoulders and hands being pulled. When your feet were being lashed, I could almost feel the burning sensation and hear your cries. You have an amazing talent to take the reader into your hell of a torture chamber but guide them with grace, compassion, and hope.

I wished Evin and Moshtarak Prisons were turn into museums to remind us of the horror of the past so we can better appreciate the beauty of life, humanity, and freedom.

Houshang Jan, we’ve never met but I hope to shake your hand some day.

God bless you and all the Iranian families who’ve been, and are being, tormented by IRI.

Sheil

—————————————————————————————————

Memories of Iran

Enduring the shah’s prisons—and those of the Islamic Republic

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703720504575377124235267304.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

By SAUL ROSENBERG

When Houshang Asadi’s feet hurt, he doesn’t have to wonder why. They’ve been that way for 25 years, since the days when he was regularly beaten in an Iranian prison. The Islamist government’s jailers knew well that the soles of the feet make an inviting target—rich in sensitive nerve endings and easily crushed bones. Memories of his imprisonment and torture in the early 1980s, Mr. Asadi says, still brought on tears every morning when he sat down to write about life before he escaped to Paris in 2003 from “the mega-prison that is today’s Iran,” as he calls his former home in the extraordinary memoir “Letters to My Torturer.”

The book would be remarkable on any terms, but it is made especially memorable by the chilling irony and heartbreaking naïveté that characterize Mr. Asadi’s tale. His first experience of being imprisoned for political reasons comes as a young communist in the 1970s, when Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s government decides he is a threat. For several months Mr. Asadi shares a cell with someone the regime also considers a threat—a warm-hearted cleric who weeps when he prays. The cellmates become friends, and, when they are separated in jail, the cleric assures Mr. Asadi that under an Islamic government—the shah’s overthrow is already being contemplated—”not a single tear would be shed by the innocent.”

After an Islamic government does seize power in 1979, the cleric, now released and indeed a prominent member of the revolutionary hierarchy, invites his idealistic former cellmate to edit the regime’s newspaper. After all, Iranian communists like Mr. Asadi had supported the Islamic revolution. But Mr. Asadi turns down the offer—he doesn’t approve of the republic’s ideology and if he accepted he “would be lying to myself and to you.”

It’s hard to know what to make of this sort of integrity, one oblivious to the true meaning of what it is opposing, what it is defending and what its costs might be. Mr. Asadi has no idea, when he declines to work for the Islamic regime, that the door he closes behind him will open only into a room with a rope hanging from the ceiling and blood on the walls. He also seems, for much of the book and perhaps even at book’s end, not to appreciate that his dear communism is similarly unforgiving whenever it acquires power and that radical Islam and communism share an urge toward totalitarianism.

The Islamic rulers’ honeymoon with the communists is brief; soon a general crackdown is launched. Thus in 1983 begins Mr. Asadi’s descent into a realm of state cruelty that makes the shah-era detentions look like child’s play. His old friend the Islamic cleric, meanwhile, flourishes during this period—and continues to do so today, for the cleric is Sayyed Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader.

Mr. Asadi is so politically guileless that when his arrest comes, he persists for some time in the belief that somehow an American-sponsored coup like the one that brought the shah to power in 1953 is under way. Instead, he spends more than two years being interrogated and tortured by the Islamists. Much of the “intimate cruelty” is administered by someone he calls “Brother Hamid.” Working through all the levels of his hatred for this man is one of the functions of Mr. Asadi’s memoir.

Mr. Asadi is beaten, whipped and hung by his wrists for hours at a time, his toes just shy of the floor. Sometimes he is up-ended so that he hangs with his nose in his own excrement. “Brother Hamid transformed me from a young idealist to the lowest form of life on earth,” he writes.

Eventually he cracks, but not before absorbing an astonishing degree of brutality, some of it for trying to “confess”—he falsely says that he spied on the regime for the British and the Soviets—without ¬implicating anyone else. Here no one can doubt Mr. Asadi’s extraordinary courage. The book ends with his release after the government apparently decided that he was too junior in the Communist Party to merit further torment. But he emerges into a country where the rulers’ paranoia has not been assuaged by the mass murder of thousands of his comrades in 1988 for their supposed danger to the Islamists’ rule.

“Later on,” Mr. Asadi writes, “the collapse of the Soviet Union, a country I had visited at the height of its power, took with it the last fragments of my beliefs. I had freed myself from myself.” He had nothing left, he says, but “love, beer, and literature.” He would continue to live in Iran for 15 years, forswearing political activity and eventually fleeing to Paris with his wife when the opportunity arose. A long-time author, editor and translator, he now writes for the Persian-language news website Rooz Online, which he co-founded.

Mr. Asadi’s dispassionate description of his experiences makes the book a permanent addition to the harrowing genre of the torture memoir. “Letters to My Torturer” is further distinguished by its precise anatomizing of the curious closeness that grows between torturer and tortured. “In the end, I began to see something of myself in my torturer, and found myself recognizing him as a human being too,” he observes. This intuition is all the more remarkable insofar as Mr. Asadi has given us an indelible portrayal of the fervent commitment to Islamism that makes his torturer pitiless.

There are some bumps in the narrative—it is not clear at some points when Mr. Asadi is addressing Brother Hamid, for instance, and whether some passages were written on command, as part of his elaborate “confession” in jail, or some years later in Paris. He also makes fugitive references to Guantanamo Bay, San Quentin and Israeli solitary-confinement cells, which suggest that, remarkably, Mr. Asadi is not quite ready to draw the distinctions between totalitarianism and democracy that his book so vividly demonstrates.

Nevertheless, Mr. Asadi has offered the world a powerful testament to what transpires in the prisons of Iran—a nightmare that the country’s radical Islamic leadership clearly would be only too happy to export.

Mr. Rosenberg is a writer and editor living in New York.

Copyright 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved